"X-Men: First Class" hits theaters as the fifth in a series of successful movies in the "X-Men" franchise, with at least two more "X" films on the horizon: "The Wolverine" and "Deadpool."

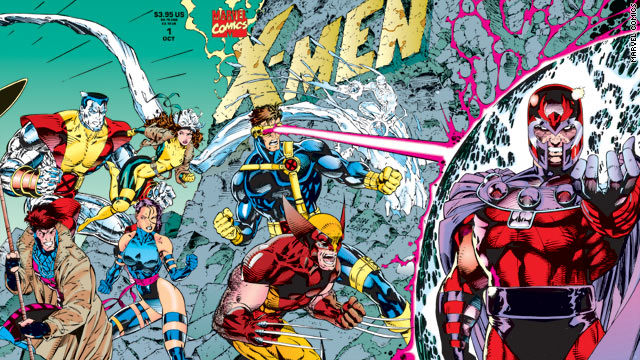

"X-Men: First Class" hits theaters as the fifth in a series of successful movies in the "X-Men" franchise, with at least two more "X" films on the horizon: "The Wolverine" and "Deadpool." The series was the second launched by Marvel Studios in 2000, following a wildly popular 1990s Saturday morning animated series, which closely followed the story arcs from decades of stories from the wildly popular comic books. Marvel Comics regularly puts out seven core "X-Men" titles, and they remain among the top-selling titles for the company.

This kind of success certainly was not the case in 1975, when Chris Claremont took over as writer for "Uncanny X-Men." At that time, it was a bi-monthly title and a perennial "also-ran," not as popular as other Stan Lee creations like Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four.

When then-editor-in-chief Len Wein noticed Claremont's enthusiasm for the characters, he asked Claremont to work on the title. "For the chance to work with those characters and a talented artist like Dave Cockrum, I said yes," Claremont said.

With the introduction of characters like Rogue, Gambit and Mystique, the development of Wolverine, and classic storylines like the "Dark Phoenix Saga," readers soon discovered (and in some cases, rediscovered) the X-Men.

So, what was it that got them hooked, and what has hooked so many since? "I wanted the characters to be memorable, just out of a sense of realism," said Claremont, "that the more like the readers they became, in familiarity in challenges, in the stresses and strains they faced, and choices they made to overcome them, the more enthusiastically the readers would bond to them, and stick around and come back for more."

Claremont described himself as being "knocked off his feet" over and over by the fans' affection for the characters. "For many of them, the X-Men were akin to real people, the conflicts the X-Men faced had resonance in their own lives," he said. "It was sort of daunting because from the inside looking out, it's 'Hey, I'm writing stories about adventures with colorful costumes, and we're all having a great time.' But it's readers bonding with people, not with images, and it became a circumstance where I, as a writer felt a responsibility to respect that relationship, and in turn come up with stories that fulfill the investment for the reader. It was not just a casual throwaway thing. If they care that much I have to give them something worth caring about."

Claremont recalled meeting one fan years ago, who was in tears. "Her husband had been willing to indulge her affection for the comics so long as it was just her, but now their children were growing up and starting to read and he was not convinced that people having adventures in skintight costumes were altogether appropriate," he said. "His feeling was that his wife would have to stop reading it, and she was heartbroken because she had an equally strong commitment to the fictional characters she had been enjoying all these years. When you come face to face with that kind of circumstance, it has to be treated with respect. It's like singing on stage and realizing you had an impact on your audience, and using that as an excuse to do your craft better than before."

Readers like iReporter "Cougar" Littlefield of Broomfield, Colorado, have been touched deeply by the X-Men in the years since. "One story that really changed me was 'The Legacy Virus,'" he said, describing the story arc that played out over several years, ending with Colossus' sacrifice and his girlfriend Kitty Pryde's exit from the X-Men.

"It helped me let go of some serious issues in my life at the time," said Littlefield. "I saw that this superhero could let go, and I realized I could let go and move forward from some things that were holding me back and really ruining my life. It was a true coming-of-age story."

The X-Men have been particularly relatable to the geek set, said Kiel Phegley, news editor of ComicBookResources.com: "Any kid that ever felt a little strange -- be they a traditional comic nerd, a theater geek, a punker, an ethnic minority or someone who self identifies as queer -- could see themselves in the struggles of the mutant heroes fighting to fit in to the normal world. Of course, it never hurt things that such a personally powerful metaphor came wrapped in stories of ruggedly sexy superpeople who spent their time falling in and out of love with each other whenever they weren't battling giant robots."

As for Claremont, he was caught up in these characters just as much as the readers were, and stayed with the X-Men titles until the early 1990s (and returned to the characters several times since). "I kept running into all these really neat people in the book," he said. "The more stories I told, the more I found I wanted to tell. There was always something left unsaid. I got hooked by my own impulse of 'Well, what's gonna happen next?' "

The characters' relatability, trials and tribulations weren't the only things that caught fans' interest. Many saw parallels between the mutants' struggles to fight prejudice and what was happening in the real world.

"The constant theme of 'people fear what they don't understand' is what defines most of America's issues, especially with racism, homophobia and anti-Semitism," said iReporter and motivational speaker Omekongo Dibinga, a lifelong fan of the characters. "Professor Xavier always talks about engaging, always talks about going to the community, and a lot of people really need to pay attention to these comic books, because I think we can learn a lot from them."

Another famous Claremont story arc, "Days of Future Past," had quite an impact on readers, such as Viktor Kereny of Los Angeles, California. "This story gave me insight into the issues of genocide and fighting for freedom," he said.

The characters of Xavier and Magneto have even been compared to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. Last year, Lee told CNN, "They were meant to emphasize the conflict between people who felt that we've got to all work together and find a way to get along, and people who feel, 'We're not treated well, therefore we're going to strike back with force!' "

When asked about the comparisons, Claremont said, regarding his early work in the 1970s, "It was too close. It had only been a few years since the assassinations. In a way, it seemed like that would be too raw. My resonance to Magneto and Xavier was borne more out of the Holocaust. It was coming face to face with evil, and how do you respond to it? In Magneto's case it was violence begets violence. In Xavier's it was the constant attempt to find a better way."

"As we got distance from the '60s, the Malcolm X-Martin Luther King-Mandela resonance came into things. It just fit."

The word Claremont uses the most to explain the X-Men's appeal, as well as comics' appeal in general, is "primal."

"The best moments in comics come from a primal image that captures the emotion and the conflict. What you add are the pieces that get you to the point and what happens next. Comics are primal, down and dirty."

So, with so many decades of being so close to these characters, could Claremont ever pick a favorite? "It's like asking a dad if you have a favorite kid," he said. "I could cheat and say Kitty... well, but Lockheed ... Nightcrawler is so cool. Jean is so ... and then there's Ororo and Scott. I can't pick one, they're far too much fun."

No comments:

Post a Comment